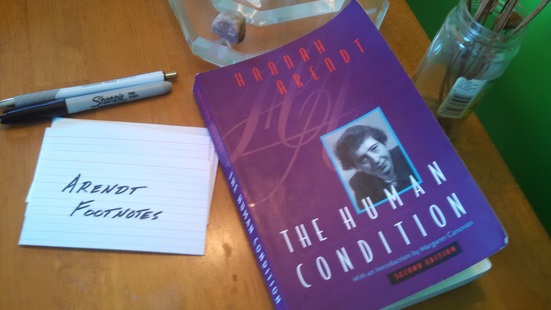

Arendt Footnotes #6, Eudaimonia

Arendt Footnotes #6, Eudaimonia Eudaimonia

Arendt enlightens the misery of blindness to our own light.

The Human Condition

Section 27: The Greek Solution

(192-3, bold added)

This unpredictability of outcome is closely related to the revelatory character of action and speech, in which one discloses one’s self without ever either knowing himself or being able to calculate beforehand whom he reveals. The ancient saying that nobody can be called eudaimon before he is dead may point to the issue at stake, if we could hear its original meaning after two and a half thousand years of hackneyed repetition; not even its Latin translation, proverbial and trite already in Rome – nemo ante mortem beatus esse dici potest – conveys this meaning, although it may have inspired the practice of the Catholic Church to beatify her saints only after they have long been safely dead. For eudaimonia means neither happiness nor beatitude; it cannot be translated and perhaps cannot even be explained. It has the connotation of blessedness, but without any religious overtones, and it means literally something like the well-being of the daimon who accompanies each man throughout life, who is his distinct identity, but appears and is visible only to others. (footnote 18)

18. For this interpretation of daimon and eudaimonia, see Sophocles Oedipus Rex 1186 ff., especially the verses: Tis gar, tis aner pleon / tas eudaimonias pherei / e tosouton hoson dokein / kai doxant’ apoklinai (“For which, which man [can] bear more eudaimonia than he grasps from appearance and deflects in its appearance?”). It is against this inevitable distortion that the chorus asserts its own knowledge: these others see, they “have” Oedipus’ daimon before their eyes as an example; the misery of the mortals is their blindness toward their own daimon.

Have a good burn!

Next Up: Republic and the 228th birthday of the US Constitution, Thursday 17 September.

Posted by Bryan W. Brickner

RSS Feed

RSS Feed